Swahili Coast, East African trade center that controlled Asia & Africa trade 12 – 15th CE

From the 8th century, the Swahili Coast on the East African coast was a location where Africans and Arabs interacted The post Swahili Coast, East African trade center that controlled Asia & Africa trade 12 – 15th CE appeared first on The African History.

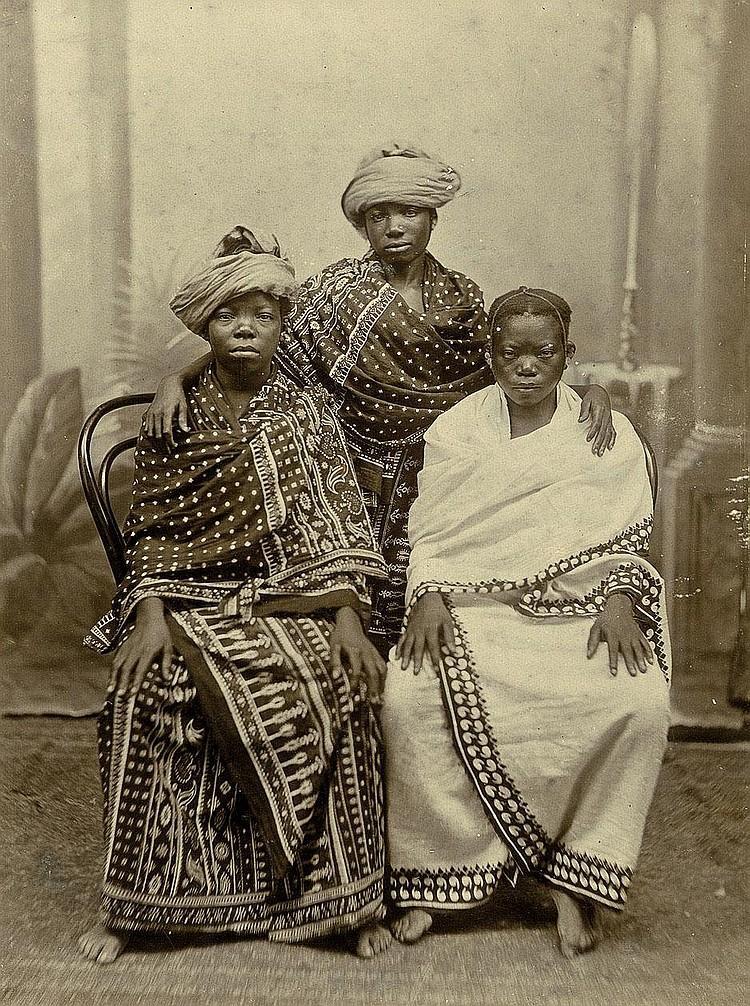

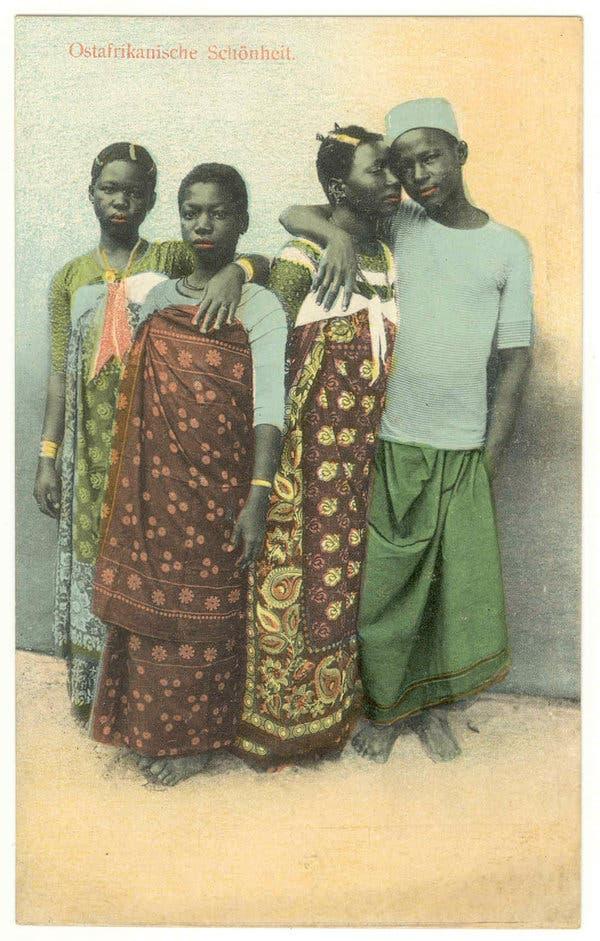

From the 8th century, the Swahili Coast on the East African coast was a location where Africans and Arabs interacted to develop a unique identity known as Swahili Culture.

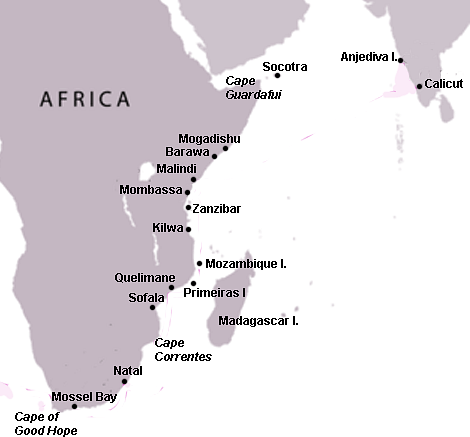

Their language is Swahili, which means “people of the shore.” Mombasa, Mogadishu, and Zanzibar were among the prominent, independent commercial cities that sprung up along the coast.

The Swahili Coast city-states dealt with African tribes as far away as Zimbabwe as well as the period’s big commercial powers across the Indian Ocean in Arabia, Persia, India, and China during its peak from the 12th to 15th centuries.

The voracious Portuguese arrived in the 16th century and devastated cities, constructed forts, and generally disrupted the perfectly balanced trading network they had come to benefit from.

Swahili

Swahili means “people of the coast” and is derived from the Arabic word sahil (‘coast’). It not only refers to the East African coastal region, which stretches from Mogadishu in Somalia to Kilwa in the south, but also to the language spoken there, a variant of the indigenous Bantu language that originated in the first millennium CE.

Many Arabic phrases were blended in later, and Swahili became the lingua franca of East Africa, despite the development of different dialects. The language is still spoken throughout East Africa today, and it is the national language of Kenya and Tanzania.

MANY EXCELLENT NATURAL HARBOURS FORMED BY SUBMERGED FORMER RIVER ESTUARIES LINE THE EAST AFRICA COAST.

Ancient Settlement

Agriculture and animal husbandry flourished among the ancient peoples of what would become the Swahili Coast, assisted by a consistent yearly rainfall and shallow coastal seas rich in seafood.

During the Iron Age, trade between the Bantu farming peoples residing along this coast began in the first centuries of the first millennium, using dugout canoes and small sailing vessels.

The existence of several coastal islands provided both shelter and convenient stopping off locations along route, as well as the extensive lines of coral reefs that protected the shallower and calmer waters between them and the mainland. Furthermore, the East African coast has a number of superb natural harbours built by buried old river estuaries.

Initially inhabiting the interior, Bantu people gradually moved to the coast in greater numbers as the second millennium progressed, establishing over 400 new settlements and building their homes out of stone – typically coral blocks held together with mortar – instead of or in addition to mud and wood.

They grew wealthy by trading coastal goods like shell jewelry for agricultural goods from the more fertile inland. When trade networks expanded along the coast, so did ideas in art and architecture, as well as language, eventually spreading Swahili to cover 1600 kilometers (1000 miles) of Africa’s coastline and establishing contacts with Madagascar, an island with a long history of cross-cultural contacts, including with Indonesia.

Arrival of Muslim Traders

The number of traders sailing the Indian Ocean increased dramatically after the 7th century, and included those from the Red Sea (and hence Cairo, Egypt), Arabia, and the Persian Gulf.

Dhows from the Arab world, with their unique triangular sails, flooded the Swahili coast’s ports. India and Sri Lanka, as well as China and Southeast Asia, were all involved in trade over the Indian Ocean.

Long-distance sea excursions were made possible by the monsoon winds, which blew northeast in the summer and south in the winter. Sea travel was, in fact, much easier and faster than land travel at the time.

As these beneficial winds got lighter and less consistent as one traveled further south, towns were smaller and less numerous along Africa’s southern coast.

Muslim traders from Arabia and Egypt began to settle permanently along the Swahili coast, particularly on the safer coastal islands, starting in the mid-eighth century. Shirazi people, originally from Persia, arrived in the 12th century.

Intermarrying was popular, and as a result of this blending of cultural traditions, the indigenous Bantu and all these outsiders blended, as did their languages, resulting in the formation of a wholly new Swahili culture.

Medieval Trading Cities

The most important of over 35 major city-states along the Swahili Coast were (from north to south):

* Mogadishu

* Merca

* Barawa (aka Brava)

* Kismayu

* Bur Gao (aka Shungwaya)

* Ungwana

* Malindi

* Gedi

* Mombassa

* Pemba

* Zanzibar

* Mafia

* Kilwa

* Ibo

* The Comoro Islands

* Mozambique

* The northern tip of Madagascar

With the exception of Mogadishu, these city-states rarely exercised political influence outside their immediate neighborhood. There was very little cultural influence in the interior of the mainland. However, because many communities were unable to produce adequate food, some sort of arrangement must have been made with indigenous tribes on the mainland, who contributed sorghum grain, rice, bananas, yams, coconuts, and other commodities.

Trade

The Swahili city-states received goods from all over Africa, especially southern Africa, where Kilwa maintained a trade emporium near the kingdom of Great Zimbabwe, Sofala (c. 1100 – c. 1550).

These items may be consumed in the cities, passed on to neighboring African communities (after payment of duties to the rulers of the towns), or shipped off the continent by sea.

In the other direction, products arrived from Arabia, Persia, and India, as well as China and Southeast Asia via these ports. The imported goods were consumed in Swahili city-states as well as traded to African villages across East and Southern Africa.

Finally, Swahili city-states produced pottery, cloth, and the lavishly ornamented siwa, the region’s traditional brass trumpet, for both their own citizens and for trade.

Goods from Africa included:

* Precious metals – gold, iron, and copper

* Ivory

* Cotton cloth

* Pottery

* Tortoise shells (principally to make combs)

* Timber (especially mangrove poles)

* Incense (e.g. frankincense and myrrh)

* Spices

* Rock crystal

* Salt

* Grain & Rice

* Hardwoods (e.g. sandalwood and ebony)

* Perfumes (e.g. ambergris which is derived from sperm whales)

* Rhino horns

* Animal hides (e.g. leopard skins)

* Slaves

Goods imported from outside Africa included:

* Ming porcelain

* Pottery from Muslim states

* Precious metal jewellery

* Silk and other fine cloths

* Glassware

* Glass beads

* Faience

Merchants traded these items under a barter system, where one product was exchanged for another, but by the 11th or 12th century, some of the larger communities, such as Kilwa, were able to issue their own copper coins. Copper ingots or cowrie shells were other routinely agreed upon money goods.

Government & Society

Swahili cities were independent from one another and usually ruled by a single monarch, although there are few data about how these rulers were chosen, except from certain incidents of one ruler naming his successor.

The cities were governed by the wealthy Muslim merchant class by the 12th century. Various officials, such as a council of advisors and a judge, aided the single monarch or sultan, who were all likely chosen from the most powerful merchant families.

The post Swahili Coast, East African trade center that controlled Asia & Africa trade 12 – 15th CE appeared first on The African History.